Coastal land loss is a cascade of geologic functions, yet in the case of Louisiana, the the cascading functions have a common catalyst: humans. Anthropogenic, or human-caused, factors for land loss have left the state playing catch up with nature. Although great work is being done to prevent further land loss, these efforts are null if we don’t acknowledge that our own, human-centric decisions are why this state now expends billions of dollars to undo generations of land loss. Louisiana’s reasons for coastal land loss include a leveed river, consequences of a petroleum industry, as well as cultural traditions and a commercial fishing industry. I believe a soundly educated public that understands Louisiana’s land loss issues is one of the most important defenses the state has to prevent detrimental affects in years to come. For that reason, I decided to do my CRCL Creative project on the effects of oil and gas navigation canals on coastal land loss.

In preparing this project I had the privilege to speak to Mr. Al Duvernay. As a lifelong resident of and sportsman in Louisiana’s coastal regions, he has witnessed rapid land loss in his own lifetime. He worked as a Geologist with Shell oil and gas company, making him both a scientific resource as well as lending his familiarity with oil and gas industries.

The Underlying Issue: A Leveed River

The land we know as coastal Louisiana is a gift of the Mississippi River. For thousands of years, the Mississippi river flowed through 31 states, picking up sediment and nutrients as it goes along, and depositing its richness in its final state, Louisiana. If you imagine coastal Louisiana as a beating heart, the Mississippi river is the aorta bringing it everything it needs.

If left unaltered, natural river systems are land-building machines. Across the span of hundreds of years, rivers deposit sediment rich water that forms land. After many years of depositing sediment along its banks, the river will flood over its banks and shift course- bringing its land-building sediment along its winding course. Before levees, the Mississippi river spent thousands of years acting like a loose garden hose- shifting from one direction to the other, releasing sediment and nutrients at every turn. This natural river system with a winding path and shifting delta is what created coastal Louisiana. Without the deposits from the Mississippi river, our coastal land would not exist.

As communities, businesses, and agriculture began to exist along the river, it became important that the river stay put. Although a shifting river means the deposition of new land along its path, it also means flooding of the communities surrounding it. Far before the Louisiana purchase, the first versions of levees along the Mississippi river were built in the early 1700’s to protect New Orleans (LaCoast.gov). In years past, flood control and levee systems have become increasingly robust. Human innovation has succeeded in keeping the Mississippi river in its current path for generations. However, this innovation comes at the cost of the sediment laden flooding that builds our land.

Without a River to deposit new land-building sediment, the most efficient way to maintain coastal Louisiana is to fiercely protect the land we already have. The natural system that created the land no longer exists to replace what we are losing.

The Calm Before the Canals:

The Before: Lets consider Plaquemines parish which lies at the southernmost tip of Louisiana, along the Mississippi river, leading to the River’s current and now permanent delta (the “mouth” of the river). Mr. Duvernay provided the below map, depicting Plaquemines parish in 1891

Keep in mind this wide open, light blue area of land. Notice the lines on this map are squiggly, undulating water ways. Make note of the inland Bays, each separate from each other and surrounded by land.

Oil and Gas Come to Southern Louisiana

Beginning in the 1930’s, petroleum companies rushed to coastal Louisiana as the extractive industry expanded into the new practice of offshore drilling. The companies were widely welcomed. They provided employment, a higher standard of living for rural communities, and gave the state a method to profit from coastal marsh and wetlands which were believed at that time to be of low ecological importance. Louisiana asked few questions of the believed harbingers of wealth and financial comfort and happily welcomed these companies into our pristine marshlands and untouched coastal ecosystems.

With the onset of offshore wells came the need for navigation. Beginning in the 1930’s and extending into the 1970’s, oil companies dredged thousands of miles of navigation canals through coastal Louisiana. These canals ripped straight lines through marshes, connecting lands and waterways that would’ve previously never met.

Below is a map of Plaquemines parish from 1960, 30 years after the dredging of these oil and gas canals. Straight lines are canals; natural waterways never form straight lines.

In the span of 70 years, the inland Bays connect, the land surrounding them is shriveled and disjointed, and straight lines riddle the map from the Gulf all the way inland to the River.

Let’s fast forward another 60 years. Below is a map of inshore fishing locations published in December of 2020 by the Louisiana Sportsman hunting magazine. This map depicts the same location as the others, although the labels are the only ways to tell:

The maps speak for themselves: land loss is occurring; rapidly and within this lifetime. Let’s say you were born in 1960, learned to hunt and fish in Delacroix with your father and grandfather when you were 10 years old in 1970. By the time you have grandchildren to bring hunting, the land where you hunted at their age no longer exists.

What do Canals Have to do With It?

Let me play attorney employed by the oil and gas industry devil’s advocate. I said it myself; land loss is a complex geologic process and the River is where the land comes from, so why are we talking about canals? If the River delta is how land is built and nourished, isn’t this land loss the fault of the levees? Wouldn’t this land loss occur as long as the river is leveed?

Coastal land loss will be a problem for Louisiana so long as the sediment from the Mississippi is not deposited where it is needed. That is the crux of the problem, but not the entirety of it. If a leveed river is like having a broken leg, the canals dredged by oil and gas companies are forcing the state to run a marathon on a broken leg. Here’s why:

Salt Water Intrusion: Much of coastal Louisiana is a freshwater system. The vegetaiton, the wildlife, and the soil are all adapted to living without salt. Oil and gas canals create connections between the salt water of the Gulf and the fresh water wetlands, Bayous, and Bays of the coast. Once salt arrives in an ecosystem, it is incredibly rare that any existing freshwater vegetation could survive. A rapid die off of vegetation results in rapidly increased rates of erosion.

Erosion: Erosion occurs when organic material is washed away. Vegetation, such as that which is killed by saltwater intrusion, is an important prevention for erosion. The dense root systems of thriving vegetation lock soil in place, preventing erosion.

Surface Area: Oil and gas canals increase the surface area of the coast line, increasing its exposure to the factors that contribute to erosion. Imagine cutting a cube of ice- the smaller pieces will melt first, right? The same applies to Louisiana’s coast.

Storm Surge: The canals built by oil and gas allow easy paths for storm waters to reach the inland areas of freshwater systems. These gone coastal marshes had a multi-tiered protection plan to weaken hurricanes: a lack of open water, dense vegetation, and a buffer between the state and the Gulf.

The Stakeholders: Residents of Coastal Louisiana

Although residents of coastal Louisiana see land loss occuring in their own lifetimes, in their own back yards, there is staunch opposition to refilling canals or diverting sediment to rebuild new land. The reasons why are complex and uniquely cultural to the region.

Many coastal residents make a living from the commercial fishing industries that harvest from fisheries adjacent to the rapidly eroding coastal lands. These fishermen stand to benefit from the land loss and salt water intrusion. Oyster fisheries, in particular, are closer to land than they were in generations past. Oysters require a very specific threshold of salinity, so as salt water from the gulf creeps closer to the land, it creates a hospitable habitat for oysters. To rebuild land in these areas means to push the fisheries out further to the gulf- making life more difficult for those who rely on the industry. A restored coast line means these fishermen would need to travel further offshore to reach their fisheries, require more fuel for longer trips, and require new refrigeration techniques on boats to prevent harvests from spoiling on the trek. As policies stand today- fishermen would foot the bill for all of these changes.

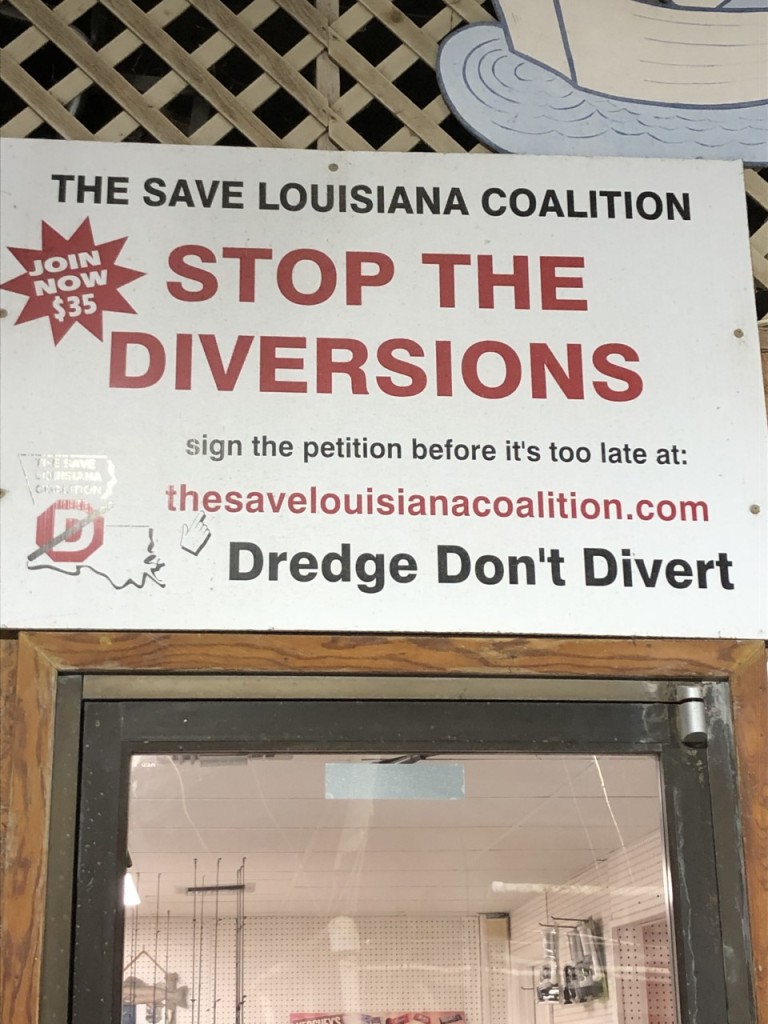

Mr. Duvernay provided important cultural context to this issue. Coastal fishermen are anything but shy in their opposition to rebuilding the land or restoring natural systems. For example, the below sign hangs proudly in a bait shop in Chalmette:

“Dredge, don’t divert”

“Divert” is in reference to the nascent sediment diversions in coastal Louisiana. These diversions aim to bring sediment through the levees surrounding the river in order to divert it to the areas hardest hit by land loss and restore them to freshwater systems. “Dredge” is in reference to canals, such as those provided by oil and gas companies. These canals also provide transportation for fisheries industries to reach the gulf easily. Commercial fishing industries want nothing to do with land restoration so long as it makes their living harder to come by.

A more complex issue comes from the oil and gas industry. The impact the petroleum industry on Louisiana could be its own post, but suffice it to say, many Louisianans preach “don’t bite the hand that feeds you” when it comes to restricting oil and gas operations in the state. The industry provided $73 billion of the state’s GDP in 2019, making it incredibly difficult to limit an industry that provides a quarter of the state’s economy. The nearly 250,000 Louisiana families employed by oil and gas companies do not want to see the industry that provides for them limited or unwelcomed in the state.

So, What Now?

According to a 1993 report from the U.S. Geological Survey, the petroleum industry is responsible for 36% of Louisiana’s land loss. Though this report has been contested by those who would benefit if it were false, it was the first credible source to place blame squarely on the shoulders of the oil and gas industries. Though the report did not incur legal responsibility, it sullied the reputation of the petroleum industries and their actions on our coast.

If you recall the map from 2020, you will see that much of the land where the canals were built is already completely gone. Refilling these canals is not possible, their damage is done. But can the state still recoup its losses? A groundbreaking lawsuit was settled in 2019, in which coastal parishes in Louisiana sued petroleum industries for such damages they’ve caused for the regions. They won. The settlement will bring $100 million to Louisiana to be used for coastal restoration. This lawsuit is one of 42 like it, so larger settlements could follow.

As Louisiana muscles ahead in its restoration efforts, refilling existing canals could be on the radar in the near future. According to an interview with Mark Schleifstein, refilling the canals would cost an estimated $335 million dollars- a small portion of the allocated $50 billion to be spent across 50 years. Although refilling has not been cemented in Louisiana’s Master Coastal Plan, it may appear in the plan for 2023. Refilling canals is an imperfect solution, however. Many of the canals lie on private land, meaning land owners would need to agree to have their canals refilled. Similarly, the opposition from fishing industries would likely provide further hindrance.

What Can You Do?

- Understand the Industries: What does the petroleum industry do for this state? What does the petroleum industry do to it? How can local fishery industries sustain themselves amidst a rapidly changing environment? How can the state support the industry that provides our much loved seafood while also providing for the prosperity of future Louisianans?

- Understand the Science: Why is land loss occurring so rapidly on our coast? In what ways will climate change increase the difficulties we face? How will our fisheries, wildlife, their habitat and our Sportsman’s Paradise, be changing in the next generations?

- Volunteer: CRCL hosts volunteer events to assist in building living shorelines of recycled oyster shells- restoring ecological functions as well as slowing land loss. Many non-profits exist in Southern Louisiana and have made land loss their focus- these people would love to build your education on our issues as well as giving you the opportunity to put your own elbow grease into solving this problem.

- Cheers for the Engineers: Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan is a marvel of engineering happing every year! CPRA meetings are live to the public. Staying current on the engineering and restoration efforts (sediment diversions are magic!) happening in our state gives a feeling of hope.

- These issues often lie within policy measures on a ballot- educated voters can change the world.

- Love Louisiana: Hunt, fish, canoe, camp, kayak, hike, eat seafood, talk to ya mama n’ dem. There’s no one way to do it- meet the people behind the culture, learn some French, eat some delicious food, go to the Frog Festival, whatever suits your fancy. The issues we face are heavily depressing, looming and scary- but our state is not! Let the beauty of a cypress swamp, the tugging of a fish on the line, or a heavy Cajun accent restore your hope. Louisiana cannot be restored by those who are lukewarm in passion; love this state, know what you’re protecting.